acute renal failure

Acute renal failure (ARF), also called acute kidney injury (AKI), is defined as an acute worsening in renal function with an increase in BUN and/or serum creatinine (SCr).

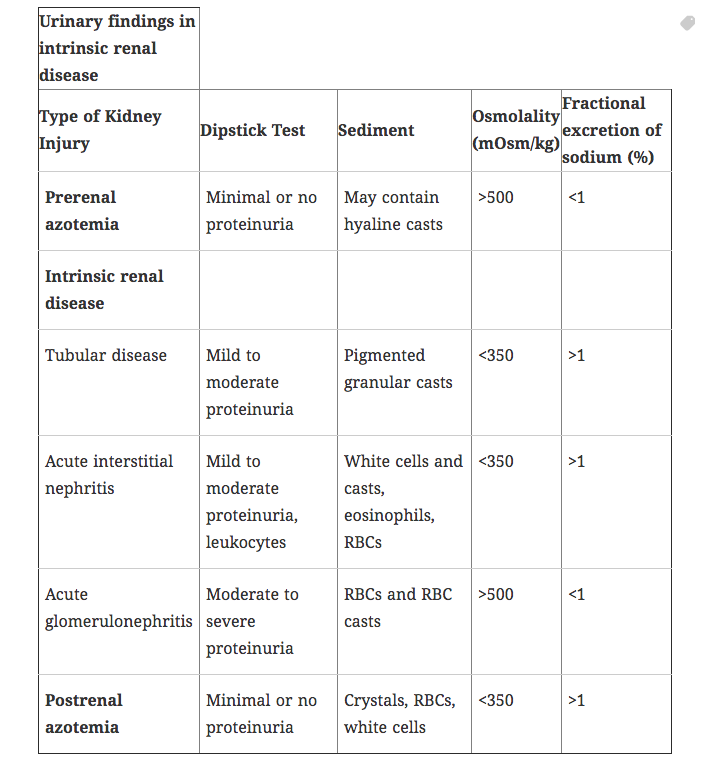

There are many causes of AKI, each divided into one of three categories: prerenal azotemia, intrinsic renal disease, and postrenal obstruction.

Prerenal

Pre-renal azotemia results from decreased renal blood flow and/or a decrease in glomerular hydrostatic pressure, leading to a decrease in the amount of nitrogenous waste products that are filtered.

Causes of pre-renal azotemia include any process that decreases renal blood flow:

- Hypovolemia

- Hypotension

- Renal Artery Stenosis/Fibromuscular Dysplasia (FMH)

- Decreased cardiac output

- Medications that interfere with glomerular filtration (ACEIs, NSAIDs)

- Elderly patients can be especially susceptible to volume depletion due to an impaired thirst response and often an inability to obtain food and water without assistance (eg, due to dementia).

By definition, the renal parenchyma is undamaged. This is key in differentiating pre-renal from intra-renal disease, in that because the parenchyma is unharmed, concentration ability is preserved.

Pre-renal azotemia that leads to renal damage (e.g. due to hypoxia) is considered to have progressed to intrinsic renal disease.

Intrinsic

Intrinsic renal disease (intra-renal) is defined as damage to the actual renal parenchyma that results in elevated levels of nitrogenous wastes.

There are three basic categories of intrinsic kidney disease based on the location of the disease: Glomerular disease, tubular-interstitial disease, and vascular disease.

Glomerular disease can result from disease to the glomerulous and/or small blood vessels. Acute glomerulonephritis is often a result of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN):

- Type I RPGN: Goodpasture syndrome

- Type II RPGN: Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, Lupus nephritis, IgA nephropathy

- Type III RPGN: Wegener granulomatosis

Tubular-interstitial disease is often caused by:

- Acute Tubular Necrosis (ATN): Can be caused by ischemic or nephrotoxic insult. Ischemic ATN is the most common cause of AKI. Microscopic examination of urine reveals epithelial casts which have degenerated to form pigmented, muddy-brown renal tubular casts in urine.

- Acute Interstitial Nephritis

Vascular diseases of the kidney include:

- Intrarenal vascular occlusion - renal artery/vein thrombosis, thrombotic microangiopathies: HUS (hemolytic uremic syndrome), TTP (thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura)

- Intrarenal vasculitis - Wegener granulomatosis

Postrenal

Post-renal azotemia (postrenal AKI) results from obstruction of urine outflow. The kidneys are intrinsically normal.

Obstruction of urethra by BPH (benign prostatic hyperplasia) is the most common cause of postrenal AKI.

Other causes of post-renal AKI include:

- Nephrolithiasis (kidney stones in urethra or impacted at bladder neck)

- Obstruction due to neoplastic invasion/extension (e.g. neoplasia of cervix, prostate, bladder)

- Bilateral obstruction of ureters (e.g. retroperitoneal fibrosis—ureters are retroperitoneal structures)

- Bilateral obstruction of kidneys (e.g. bilateral staghorn stones)

Patients often present with complaints related to the underlying cause of the acute kidney injury. Possible symptoms include:

- Fatigue

- Anorexia

- Nausea

- Oliguria

- Hematuria

- Flank pain

- Altered mental status

NOTE: The most common symptoms of AKI are weight gain and edema due to a positive water and sodium balance.

A history, physical, and lab findings are critical to finding the underlying cause of acute kidney injury (e.g. dehydration, medication use, urinary symptoms). It is important to note that AKI may present as oliguric, anuric or nonoliguric.

Diagnosis

Imaging can help diagnose the underlying pathology (e.g. stones, BPH, vascular disease):

- Ultrasonography (kidney size/hydronephrosis, hydroureter)

- CT Scan (nephrolithiasis)

- Renal arteriography (renal artery occlusion)

- Renal biopsy (if suspicion for glomerulonephritis or AIN)

The treatment of acute kidney failure mainly depends on the underlying condition. Some general treatment measures include the following:

- Prevention (avoid nephrotoxic agents or those that decrease renal blood flow)

- Correct underlying fluid imbalance (IVF v. diuresis)

- Correct underlying electrolyte imbalance (i.e. hyperkalemia, hypocalcemia)

- The patient may need dialysis if uremia is prolonged and symptomatic or if electrolyte/acid-base imbalances are refractive to therapy

Treatment

Treatment for pre-renal AKI mainly focuses on maintenance of euvolemia and treatment of the underlying disorder. A swan-ganz catheter may be placed if the patient is unstable.

Treatment for intra-renal AKI is mostly supportive, especially once acute tubular necrosis has developed. Other helpful methods include elimination of offending agents and diuresis if the patient is oliguric.

Immunosuppressive medications may be helpful if the cause is determined to be related to glomerulonephropathy or vasculitides.

Postrenal AKI is sometimes treated with bladder catheterization or surgical removal of the obstructing pathology.

The prognosis in acute kidney injury (AKI) is generally good, with more than 80% of patients recovering completely.

In general, the prognosis decreases with increasing age and severity of AKI.

The most common cause of mortality in AKI is infection, accounting for up to 75% of deaths. The second most common cause involves cardiorespiratory complications.

ATN

There are 2 major categories of acute tubular necrosis (ATN): Ischemic and nephrotoxic. Regardless of etiology, the pathophysiology of ATN involves:

- Disturbances in renal blood flow

- Tubular injury

Ischemia

For example, consider the pathophysiology of ischemic ATN—renal ischemia causes:

- Intrarenal vasoconstriction (net effect = afferent arteriolar vasoconstriction) → ↓ GFR → oliguria

Damage of tubules in outer renal medulla, especially the straight portion of proximal tubule and thick ascending limb of Henle’s loop (the two parts of the nephron that are most susceptible to hypoxic injury due to high ATP demand) → renal tubular cell necrosis and detachment from the basement membrane → luminal obstruction by pigmented renal tubular cell casts (Tamm-Horsfall protein + entrapped cells) → ↑ intratubular pressure → ↓ GFR → oliguria.

Ischemia causes intrarenal vasoconstriction (net effect = afferent arteriolar vasoconstriction) by 2 different mechanisms:

- Ischemia → loss of tubule cell polarity → redistribution of basolateral Na-K-ATPase to luminal tubular cell surface → ↑ Na delivery to distal tubule → intrarenal vasoconstriction via a paracrine mechanism

- Ischemia → endothelial damage → ↑ vasoconstrictors (endothelin) (vasoconstrictor) and ↓ vasodilators (NO, PGI2) → intrarenal vasoconstriction

Ischemic ATN is most commonly caused by pre-renal failure, resulting from anything that compromises renal perfusion, including:

- Effective circulating blood volume (preload):

- Hypovolemia—eg, vomiting, diarrhea, burns, hemorrhage, dehydration, diuretic overuse

- Systemic vasodilation—eg, septic shock

- Cirrhosis (↓ albumin production → ↓ colloid oncotic pressure → → ↓ intravascular volume)

-

↓ Cardiac output—e.g. CHF (congestive heart failure), cardiogenic shock

-

NSAIDs (↓ PGI2 → ↓ vasodilation of afferent arteriole → ↓ GFR) or ACE inhibitors (↓ angiotensin II → ↓ vasoconstriction of efferent arteriole → ↓ GFR) can precipitate prerenal failure in patients who already have poor renal perfusion.

Nephrotoxic

Aminoglycosides are the #1 cause of nephrotoxic ATN. Other etiologies include:

- Amphotericin B

- Cisplatinum

- Heavy metals: lead, mercury

- Radiographic contrast media

- Gram negative sepsis

- Myoglobulinuria as a result of trauma / crush injuries or intense exercise (exercise-induced myoglobinuria)

Mechanism of nephrotoxic ATN:

- Tubular toxicity

- Myoglobin precipitation and tubular obstruction

- Direct injury to proximal convoluted tubule from gentamicin, mercuric chloride or ethylene glycol (antifreeze). Note, most other drugs cause an interstitial nephritis.

- In ethylene glycol acute tubular necrosis one would see massive intratubular oxalate crystal deposits with a polarized light.

Phases

Regardless of etiology (ischemic vs. nephrotoxic), ATN is characterized by 3 phases:

- Initiation phase

- Maintenance (oliguric) phase

- Recovery (polyuric) phase

Initiation phase (first 36 hours):

- Inciting ischemic event or nephrotoxin exposure → slight ↓ in urine output with an ↑ in BUN.

Maintenance (oliguric) phase:

- Sustained oliguria (40-400mL/day).

- ↑ ECF (extracellular) volume → can be associated with weight gain, edema, pulmonary vascular congestion.

- Hyperkalemia may or may not be present. → EKG changes (peaked T waves, depressed ST segment, prolonged PR interval, wide QRS complex), heart block, arrhythmias (eg, ventricular fibrillation) → ↑ risk of sudden cardiac death.

- Retention of H+ and unmeasured anions (sulfate, phosphate, urate) → ↑ anion gap metabolic acidosis.

Recovery (polyuric) phase (2-3 weeks after inciting event if patients survive the oliguric maintenance phase):

- Brisk diuresis (up to 3L/day) → urinary loss of K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, PO43- (because the renal tubules are still damaged at this point).

- Hypokalemia (one of most serious complications of recovery phase of ATN) → EKG changes (flattening or inversion of T waves, U waves, depressed ST segment), premature atrial/ventricular contractions, arrhythmias (eg, atrial fibrillation).

- Renal tubular function (concentrating ability) eventually recovers → BUN and serum Cr return to baseline.

The diagnosis of acute tubular necrosis is often one of exclusion of other causes of acute renal failure (ARF); in the majority of cases of ATN there is often a predisposing factor (e.g. contrast dye, aminoglycoside antibiotics, and/or rhabdomyolysis).

Urinalysis may show muddy brown granular casts (very common presentation) or be benign. The fractional excretion of sodium in most forms of ATN > 3. Exceptions can include contrast and rhabdomyolysis: the FeNa may be less than 1 in these disorders (due to intense renal vasoconstriction).

Treatment

The treatment of acute tubular necrosis is often supportive and often depends on identifying the underlying cause and treating it (e.g. fluids for rhabdoymolysis).

- Avoid use of nephrotoxic medications if at all possible.

- If at all possible avoid the use of dye in someone with CKD to reduce the risk of dye-induced nephropathy.

- If the kidney function continues to worsen, dialysis may be needed.

- During the diuretic phase of ATN, monitor electrolyte levels and volume status closely.

Acute tubular necrosis is the most common cause of intrarenal acute kidney injury (AKI). Recall that AKI is defined as an abrupt ↑ in serum creatinine or an abrupt ↓ in urine output.

AIN

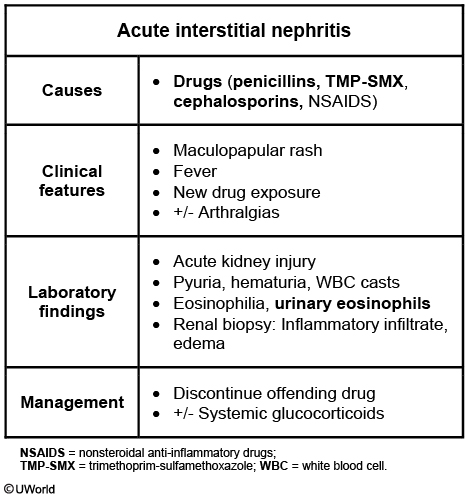

Acute interstitial nephritis is an acute inflammation of the renal interstitium (edema + prominent mononuclear and eosinophilic infiltrate) that resolves following treatment of the underlying cause.b

Interstitial nephritis is seen with the use of many drugs, remembered with the mnemonic "Please Note All Drugs that Can Possibly Scar Renals”

- Penicillin derivatives—eg, methicillin, ampicillin

- NSAIDs

- Allopurinol

- Sulfa-derived Diuretics—eg, thiazides, furosemide, acetazolamide

- Cephalosporins

- Proton pump inhibitors

- Sulfonamide antibiotics—sulfamethoxazole, sulfisoxazole

- Sulfasalazine—used to treat Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis

- Rifampin—RNA polymerase inhibitor used mainly to treat TB

Heavy metals and toxins can cause interstitial nephritis:

- Cadmium

- Lead

- Copper

- Mercury

- Toxins from some mushrooms

Interstitial nephritis can also be caused by systemic diseases and pathologies:

- Infections (Streptococcus spp., Legionella pneumophila)

- Sarcoidosis

- Amyloidosis

- SLE

- Myoglobinuria

- High uric acid levels

Acute interstitial nephritis presents acutely with symptoms of acute renal failure, as well as:

- Fever

- Rash

- Nausea and vomiting

- Malaise

Acute interstitial nephritis will result in an increase in creatinine and eosinophilia.

Urinalysis will often show granular and epithelial casts and wbc casts from the shedding of renal tubular cells.

A biopsy of the kidneys will show infiltration of inflammatory cells throughout the interstitium as well as tubular cell necrosis.

There are many serious complications of interstitial nephritis, including:

- Acute tubular necrosis

- Acute or chronic renal failure

- Renal papillary necrosis

In addition to removing/treating any underlying cause, treatment of acute interstitial nephritis is mostly supportive.

If severe enough, corticosteroids can also be useful.